Playing the Handicaps at the Cheltenham Festival

There is no doubt which is the most anticipated race meeting of the UK season and, even during a pandemic when the action is played out in front of deserted stands – perhaps especially at such a time – a wagering audience of millions will be glued to their goggleboxes, you, and me amongst them!

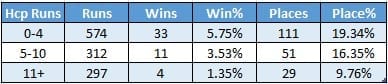

In what follows, I’ll attempt to unearth a few commonalities – positive and negative – based on the results of handicaps at the last twelve Cheltenham Festivals (2009 to 2020). For research purposes, I have ignored the Fred Winter / Boodles, a four-year-old only handicap hurdle, and also the Cross Country Chase which was a handicap until 2015 before converting to a conditions race from the following year.

That leaves 108 handicaps – 60 chases and 48 hurdles – from which to establish patterns. My intention is to look at over-arching patterns, and in some cases to break them down by obstacle type. I will generally use each way strike rates which I believe to be slightly more reliable when looking at smaller datasets. Research has been conducted using Geegeez Gold’s excellent (well, I would say that, wouldn’t I?!) Query Tool.

Right, let’s get to it.

Festival Handicap Performance by Experience

I began by researching the impact of age but ended up feeling that relative experience might be more material; so, I tracked them both, age first.

Unsurprisingly, younger horses have fared better. Of the 108 handicaps in the sample, 103 were won by horses aged nine or younger at a 4.75% win rate (18% each way strike rate). Meanwhile, the double-digit veterans scored at a rate of 1.57% and placed just 12.5% of the time.

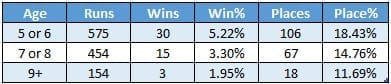

Horses go chasing later than they do hurdling so it ought to be logical that chase winners would have been older than hurdle winners. These are the figures for handicap hurdle runs, wins and places by age:

And these are the equivalent figures for handicap chases:

The message is crystal clear: you need to have a very good reason to bet an older (relatively) horse in Festival handicaps. They do win, but far less often than younger rivals.

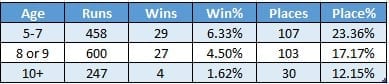

Another way to approach this is through the prism of experience, by which I mean number of runs over the obstacle type.

Here the theory is that fewer runs mean less opportunity for the handicapper to accurately assess ability.

These next tables articulate that, again, hurdles first and only including UK and Irish runs – some horses will have previously raced in France or elsewhere:

This time there is not a perfect correlation on the win percent figures, but there is on the place percentages.

Regardless, it is again the case that more ‘exposed’ runners (specifically those with 11+ UK or Irish hurdle runs) have fared barely half as well as those with less form in the book.

It is the same story in handicap chases with 80% of such races (48 of 60) since 2009 having been won by a horse which had had no more than ten UK/Irish chase starts.

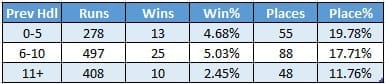

One final point on experience relates to the number of runs specifically in handicaps.

While it seems less relevant in chases, where horses have generally shown close to their level over the smaller obstacles, those nascent handicap hurdlers are very much of interest.

There is, naturally, overlap between some of these cuts of the data, but the message is always the same: less is more, whether you look at age or runs by obstacle/handicap.

Festival Handicap Performance by Market Factors

‘Market Factors’ is a grandiose term for odds and odds rank, i.e. position in the betting lists.

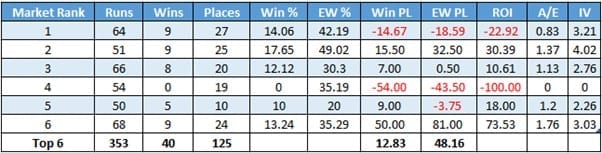

There is no obvious reason for a distinction between hurdles and chases here, so we will consider them as a job lot.

It struck me that in recent seasons, there have been less big-priced handicap winners with the emergence of any number of well plotted high class entries from the powerhouse Irish yards.

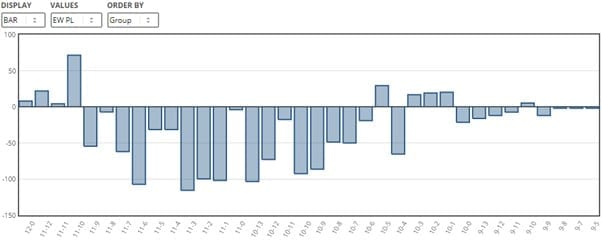

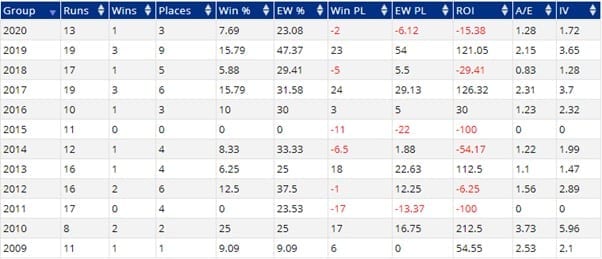

The next table shows performance of handicap runners priced in single figures, that is 9/1 or shorter, by year:

It is a visual that speaks well for itself!

When looking at odds rank, the picture is equally clear.

In the period from 2015 to 2020 (six Festivals, 54 qualifying handicaps), a blind profit would have been achieved from backing the top six in the betting at SP:

What is staggering is that 40 of the 54 handicaps (excluding Fred Winter/Boodles and Cross Country as was) were won from the 353 horses which comprised the top six market ranks. (Each position included some joint ranks, hence the variation in number of runs).

That’s 74% of the handicaps won by 29% of the runners.

At the most recent three Festivals, 22 of the 27 winners were in that top six market rank cohort: more than four-fifths of winners from less than three-tenths of runners!

Who knows whether the trend will continue?

And who’d be a bookmaker if it does?!

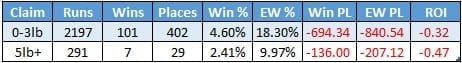

Festival Handicap Performance by Weight

Weight stops trains, as they say, but less weight has never enabled slow horses to not be slow, which is why higher weighted horses typically hold sway in handicaps, something as true at the Cheltenham Festival as everywhere else.

This is one of my favourite charts, showing each way profit and loss performance by card weight (i.e., the weight denoted on the racecard, excluding jockey claims).

There are two clear areas of profit – at the top and bottom of the weights – and each has a logical argument to be made for it. Here goes…

The top weights have already been touched upon above: they’re simply the best horses in the race and the weight does not stop them proving it in spite of what is demonstrably a disbelieving wagering public (hence the attractive profit).

The bottom weights – those still in the handicap proper (i.e., 10-01 to 10-03) – may have a lot more to offer having snuck in at the foot of the handicap, but importantly are not running from out of the handicap.

That’s more tenuous than the top weights theory and, in truth, I’m not convinced myself that it’s anything other than coincidence. But it is interesting all the same, so I thought I’d share.

Backing horses carrying 11-10 or more in Festival handicaps has been a profitable strategy, as the following summary line attests:

Here is the year by year breakdown, with 2011 and 2015 reminding us that it is far from a bombproof strategy!

Festival Handicap Performance by Headgear

Much has been written about the impact of headgear, and my going in position was that it’s an almost universal negative: very, very few horses begin their career accoutred by cheekpieces or blinkers or what have you. They ‘earn’ them by running below expectations, and most continue to run below expectations when equipped with headgear, simply because they are not very good.

This observation holds water up and down the ability spectrum, because handicaps are always about relative performance within an evenly matched (ostensibly, at least) group of equine athletes. Naturally, then, it stands up at Cheltenham also.

But there are a couple of exceptions, one of them a shock, as you’ll see in the below table, sorted by each way strike rate.

There are some very small sample sizes here, so care must be taken, but the top three results – all placing 25% or more of the time – involve a tongue tie.

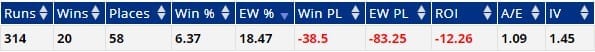

Moreover, horses wearing a tongue tie with or without other equipment have a 6.37% win and 18.47% each way strike rate.

That is higher than the ‘no equipment’ control group for both win and place; and, while it is not enough to score a blind profit, it is a notable add-on with such runners winning 45% more often than they might be expected to (IV 1.45).

What surprised me – really surprised me, actually – is the performance of runners wearing blinkers, with or without additional equipment.

Because of the sample sizes, I wouldn’t get carried away by any of this; but I’ll certainly not be put off a blinkered horse in a Festival handicap, especially if it is also tongue tied.

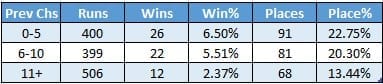

Festival Handicap Performance by Jockey Claim

The value of a conditional jockey’s claim is often mentioned in reverential terms and, of course, some talented riders are well worth their discount (as discussed in last month’s article). But, when the heat of battle is at its most intense, do we want experience or a touch less weight?

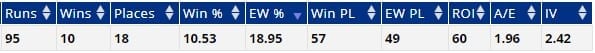

The data says exactly that: we want experience or a touch less weight; specifically, three pounds.

The table above includes six, eight and ten pound claims which are available to riders in the Conditional Jockeys’ Handicap Hurdle.

They are tiny samples, all losers, and are readily excluded from consideration.

That leaves two distinct groups. Senior jockeys and those claiming three pounds win almost twice as often as less experienced riders and make the frame at roughly the same double rate.

I’d generally be prepared to let an inexperienced rider beat me, especially given there has only been one such 5lb+ claiming jockey win at the Fez since 2014, and that was in last year’s Kim Muir, a race for amateur riders.

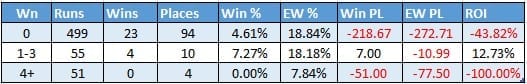

Festival Handicap Performance by Wind Surgery

One of the more interesting elements Gold subscribers can analyse in the Query Tool are wind surgery angles.

This is a little tricky with the Festival, because Irish runners are not required to declare such intervention in their homeland. However, they do have to disclose wind operations when racing in UK, as do all British-trained runners.

This information came into the public domain only since 2018 so we have just three Festivals with which to work, but a notable pattern may be emerging:

‘Wn’ means number of runs after a wind op, where 0 means a horse has not had a wind op, 1 means first time after a wind op, and so on.

Looking at each way percentages, it is at least apparent that recent wind surgery does not harm a horse’s chance in a Festival handicap; looking at win percentages, it may be that recent intervention is a positive, though again we need to be very careful of the sample size.

What we don’t know is how many of the 499 W0 runners were Irish horses which had had wind surgery prior to their most recent start and, therefore, were not required to declare it to the British authorities.

Hopefully, someday soon, the Irish regulator will also publish this information.

Summary

You don’t need anybody to tell you how difficult Cheltenham Festival handicaps are, but in the above are a few pointers towards positive and negative themes.

I would be inclined to mark up a horse for being young and/or unexposed; being well fancied; being at the top of the weights; and maybe for having recently had wind surgery or for it wearing a tongue tie and/or blinkers.

Conversely, I’d mark down a horse that was older/exposed; was a long price; or was ridden by an inexperienced claiming rider. Either way, there will still be plenty to do in order to unearth a winner or three!

Matt Bisogno

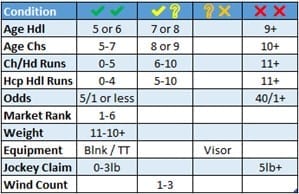

P.S. Here’s a handy cut out and keep guide to my Cheltenham Festival handicap pros and cons.

The above was researched using the Query Tool, a part of Geegeez Gold’s multi-award-winning service. Learn more at geegeez.co.uk

Featured Image: (CC BY 4.0) – https://www.flickr.com/photos/43555660@N00